By Litzi Aguilar

China has a long history of producing ceramics, dating back over ten thousand years. It began as pottery, the process by which the artisan transformed ordinary material like clay into something beautiful. From pottery came the art of porcelain. Many are familiar with the saying “fine china”, a direct reference to the fine ceramics of China exported to the Western hemisphere between the Song dynasty (960 –1279) and the Ming dynasty (1368 –1644).

One of China’s most used and improved materials is porcelain. Artisans used the earliest form of this material during the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE), otherwise known as the beginning of the Bronze Era in China. This prototype, called proto-celadon, gave off a blue-grey appearance compared to today’s porcelain. The porcelain we know was made with kaolin or kaolinite as the primary ingredient. This ingredient is the material that gives porcelain its white and translucent appearance.

The classic look of many of these porcelain ceramics is the white base with the blue glaze. There is Famille Rose, which has a white base with pink floral designs. Next, there is Famille Verte, which is mainly green with blue and orange highlights. The next look is called Canton, which is decorated with human figures, birds, and insects in color palettes of green and pink, then blue and gold. Other kinds of looks created with developed techniques give ceramics an all-black look or a cobalt blue with gold highlights.

By the eighth century, China began exporting its porcelain ceramics, starting with the Islamic world and moving to the rest of Asia. Then, by the thirteenth century, production of the finest porcelain was centered in a city called Jingdezhen, where kaolin deposits were plentiful compared to others. These were specifically made for the imperial court’s use. By the sixteenth century, China began trade with Europe, where these porcelain ceramics became immensely popular. The most common pieces traded were the classic blue and white look with river scenes or pieces decorated with Famille Rose or Verte color palettes.

Since inland access was limited, the Europeans attempted to reproduce the body and decoration on Chinese ceramics. They used soft paste porcelains such as bone china to mimic the look of genuine porcelain. Because soft paste porcelain was not fired at high temperatures, the way true porcelain was, the colors were less clear, and the glaze did not hold. It wasn’t until the eighteenth century, in Messein, that a recipe consisting of kaolin and alabaster, which emulated true porcelain, was created.

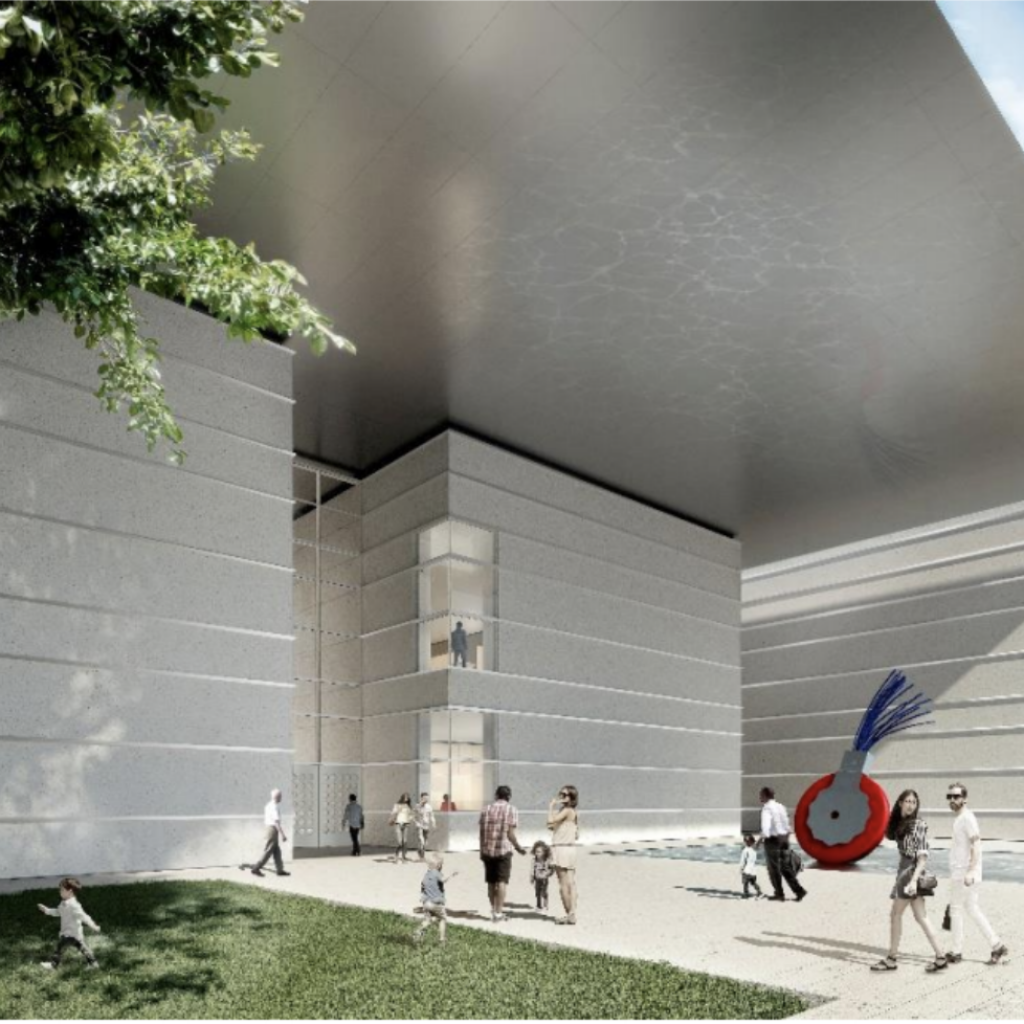

Porcelain was the fruit of China’s working class, and to this day, it is still being treasured by the rest of the world. Not only is it a work of art, but it also played a huge part in China’s trade with the outside world, changing the lives of others culturally and economically. One of the best places to visit to see these ceramics is the Norton Museum of Art. There are two separate exhibits showcasing Chinese art, including porcelain ceramics. So, take a family member or friend who might be interested in these works and take a chance to admire the long-deceased artisans’ masterpieces.